British Night Bombing Innovations

The following article is drawn from our latest book The Bomber Offensive and discusses innovations in British night bombing techniques in 1942. You can download the full book in PDF or on Amazon Kindle and the full book and accompanying interactive materials is also available to all our members as part of the larger European Air War online course. Click the button below to learn more about the full book and online course. If you have any questions about membership, email us at info@warfaremastery.com.

TEETHING AND EARLY MISTAKES (MID 1936 - LATE 1941)

It is possible to analyze the effectiveness of any bombing campaign in terms of four key elements: targeting, survivability, accuracy, and bomb damage. In order to be effective, campaign planners first need to decide what to target. In order to bomb the chosen targets, the bombers must first survive the trip and then the bombs need to fall accurately. Accuracy encompasses both accuracy in navigation so the bombers can actually find the target, and then accuracy in the bombing itself. Finally, the bombs need to do adequate damage to the target to achieve mission objectives. Implicit in the importance of bomb damage is the ability to accurately assess that damage in order to drive future planning and decisions.

The early British bombing efforts would fall short in all four of the elements just described. By December of 1940, the RAF had begun to transition to industrial targets such as the German oil supply. Some raids also focused on “morale” bombing of population centers, coinciding with German attacks on London during the “Blitz.” Clearly, there was still a notable absence of a coherent or comprehensive targeting plan.

The RAF also faced challenges in terms of survivability. Early daylight bomber raids proved to be more costly than expected, which triggered a decision to transition to night bombing. At this point in the war, night-fighter technology was still largely undeveloped and air defense capabilities in general were seriously diminished during hours of darkness. After adopting the new night bombing tactics, casualties among British bombers and crews dropped to an acceptable level.

While the transition to night bombing improved survivability, it caused a corresponding drop in accuracy in terms of both finding the target and hitting the target. Selectively ignored by leaders who were eager to both prove the effectiveness of air attack and provide encouraging headlines on the home front, this inaccurate bombing continued for over seven months until August of 1941 when Lord Cherwell, Winston Churchill’s scientific advisor, issued the Butt Report which revealed that on average, only one-third of RAF bombers hit within 5-miles of the target.

A Handley Page Halifax Mk. III four-enginged bomber

Finally, early bombing efforts also fell short in terms of the overall damage caused by the bombs. At the start of the war, the majority of British bombers had no more than two engines and were thus limited in the size and/or number of bombs they could carry. The four-engined Handley Page Halifax flew its first combat mission in March of 1941, but it would take time to field the Halifax in adequate numbers. It was not until the arrival of the Avro Lancaster to the fight in March of 1942 that the British capacity to drop heavier bomb loads began to grow significantly. In the meantime, limited payload capacity meant a limited return on investment for each dangerous mission.

REFINEMENT OF NIGHT BOMBING (EARLY 1942 - MID 1942)

A painting by W. Krogman depicting the first “thousand-bomber” raid on Cologne, Germany of 30-31 May 1943

After the release of the Butt Report in August of 1941, the RAF had no choice but to snap out of its voluntary denial of poor performance and begin to seek ways to improve in all four areas: targeting, survivability, accuracy, and bomb damage. As already explained, RAF leaders faced a dilemma when it came to the tradeoffs between accuracy and survivability. One way to potentially improve both navigation and bomb accuracy was to transition to daylight bombing. However, experience had proved that daylight raids incurred an unacceptable, and potentially unsustainable level of casualties.

Faced with this dilemma, there were two possible solutions. First was to improve navigation and bombing accuracy at night. The second was to improve the survivability of bombers in the day. One obvious approach to this second solution was to improve the capabilities of fighter escort so that fighter aircraft could protect bomber formations from enemy interceptors during the day.

The problem of fighter escort contained within it yet another dilemma. A fighter that carried enough fuel to accompany the bombers on the long journey to the target and back would by necessity be heavier and less capable in air-to-air combat. Enemy interceptors had no such range requirements, would surely best the heavier, less-capable escorts and move on to savage the bomber force. British scientists and aircraft designers concluded that developing an effective, long-range escort fighter was either impossible or overly difficult. Thus, British technological and tactical innovation focused on improving night bombing capabilities.

Sir Arthur Harris took over RAF Bomber Command in February of 1942 and implemented his new “area bombing” approach focused on German cities.

It was not until Sir Arthur Harris took over bomber command in February 1942 that this evolution in night bombing really began to take shape. Harris brought with him a new targeting approach that focused on generalized, mass destruction of German cities or “area bombing.” Harris believed that the greater volume of overall destruction would end up having a more powerful strategic effect than more surgical approaches to targeting. Area bombing of urban centers would still impact German industry, commerce and transportation but would simultaneously “de-house,” demoralize and disrupt a large percentage of the German work force and general population. Thus, in Harris’ view, his new approach would offer a greater overall contribution to the war effort than previous bombing campaigns.

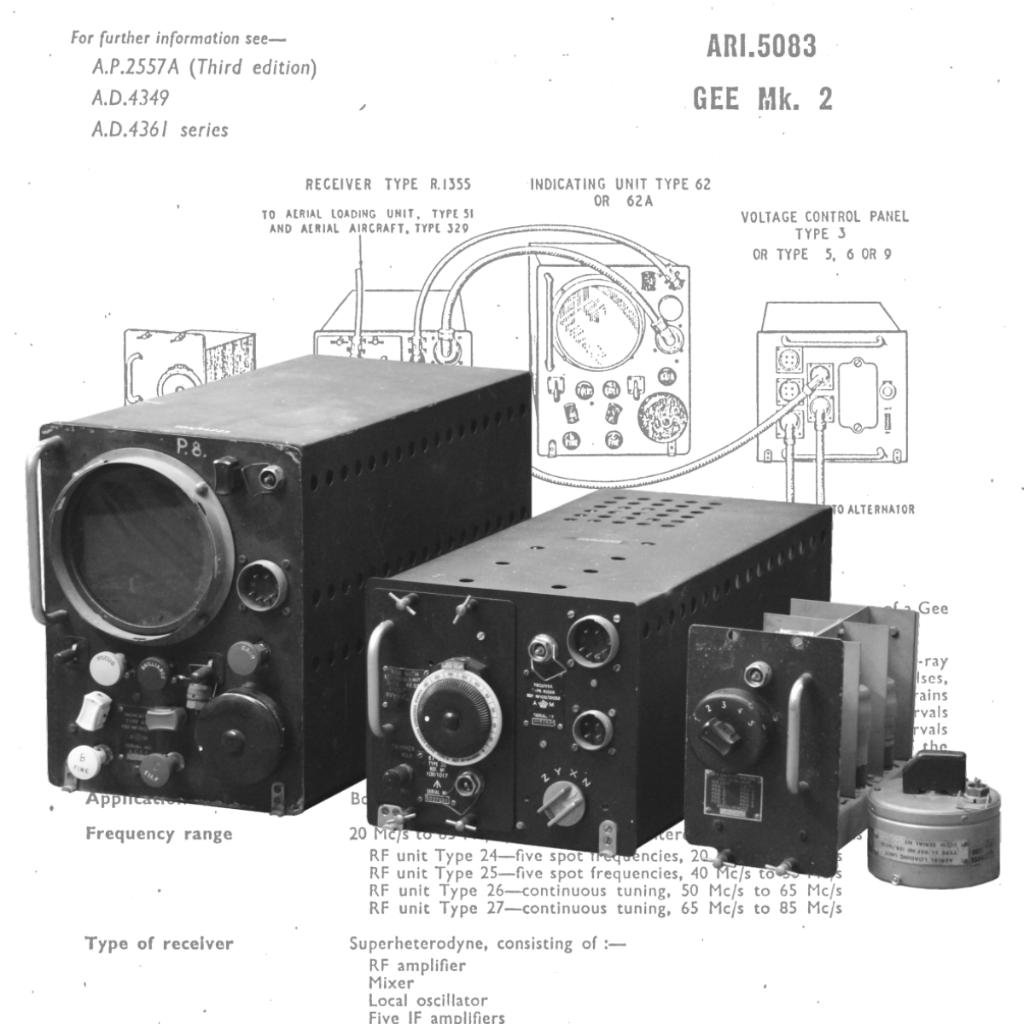

The decision to focus on bombing cities also helped solve the accuracy problem. Cities were large targets that were both easier to find and easier to hit with bombs. In March, one month after Harris’ arrival, the RAF took another leap in improving navigational accuracy by employing a new hyperbolic radio navigation system codenamed Gee. Three transmitter stations at dispersed, known locations would transmit a simultaneous signal. A radio receiver on the bomber aircraft could then plot the bomber’s position by measuring the time gap between the receipt of each signal. This system improved navigation at night and in bad weather when cloud cover made it difficult to identify landmarks on the ground.

Components of the Gee navigation system carried onboard the aircraft including the indicating unit (left) and receiver (right)

In addition to serving as a navigational aid, Gee was precise enough to provide a reference for bomb aiming/release and allowed for “blind” bombing in bad weather and limited visibility. While it did not offer enough accuracy for precision bombing, it was reasonably accurate against larger, area targets. However, Gee only had a range of approximately 350-miles which meant it barely extended beyond the Rhine River. Thus, for bombing targets deeper inside Germany, Gee was only helpful as a navigational aid during the first legs of the journey.

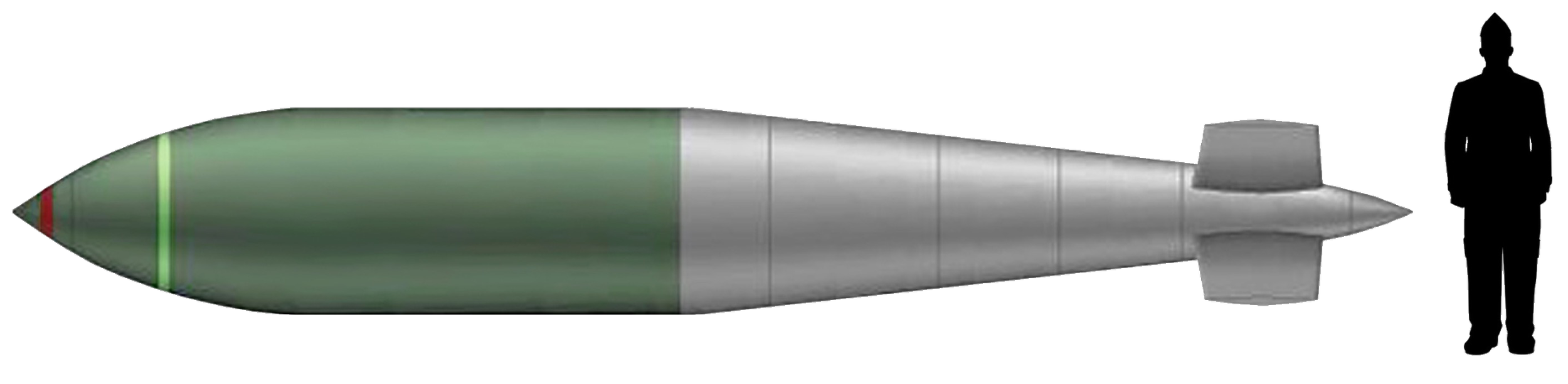

Finally, at almost the same time that Gee became operational, the RAF launched its first attacks with a new four-engined bomber that would become one of the most effective Allied bombers of the war: the Avro Lancaster. The Lancaster could carry a heavier bomb load than its counterparts and its large bomb bay could accommodate special weapons like the “Tallboy” bomb that was capable of damaging or destroying fortified targets that were impervious to smaller bombs. Thus, the arrival of the Lancaster offered a marked improvement to the RAF’s bomb damage capabilities.

The Avro Lancaster’s extra large bomb bay was able to carry the special “Tallboy” bomb, which was 12,000 lbs and 21-feet long

With this new targeting focus and improved capabilities, Harris intensified his bombing campaign and began to achieve positive results, redeeming Bomber Command from the embarrassment of the Butt Report. By May of 1942, Harris began launching “Thousand Bomber Raids,” starting with the May 30-31 attack on Cologne. While bomber command suffered substantial losses on the raid, the casualty rate was determined to be sustainable. More importantly, the overwhelming destruction caused to the city convinced many leaders and decision makers of the effectiveness of Harris’ strategic approach.

Harris’ area bombing concept and the associated simplification of navigation and aiming problems, combined with improved night navigation technologies and the greater bomb load carried by new four-engined bombers had pulled Bomber Command out of its early teething phase. While many still questioned the actual effectiveness of area bombing, it was difficult to deny that the RAF had achieved a substantial improvement. This phase would continue until the arrival of the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) would again change the battlefield equation and bifurcate the combined bomber offensive into two distinct efforts, night bombing and daylight bombing.

We hope you enjoyed this short article on the British Night Bombing Innovations. This article is drawn from our interactive online course on the European Air War and the companion book “The Bomber Offensive.” You can download the full book in PDF or on Amazon Kindle. Click the button below to learn more about the full book and online course. If you have any questions about membership, email us at info@warfaremastery.com.